Double Edge Sword of GLP-1 Therapies

GLP-1 and Dual Incretin Agonists in Obesity Management: The Double-Edged Sword of Metabolic Recoil

John Sciales, M.D.

Director, CardioCore Metabolic Wellness Center

"Getting to the Core… the Path to Wellness"

Abstract

Incretin-based therapies—namely GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual GLP-1/GIP agonists—have shifted paradigms in obesity and cardiometabolic disease, providing weight loss comparable to bariatric surgery and improving metabolic health. Yet in real-world practice, insurance-driven discontinuation post–goal weight often triggers potent physiologic responses—lower basal metabolism, heightened hunger, fat-primed adipose tissue—that drive rapid, fat-predominant regain. This “metabolic recoil” is underreported and underappreciated, jeopardizing long-term outcomes and increasing risks for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Psychiatric populations, particularly individuals with bipolar disorder, are especially vulnerable. We present this evidence through the analogies of the “hibernating bear” and the “double-edged sword,” reframing weight loss as the initiation—not the completion—of a sustained cardiometabolic health journey.

Introduction

Obesity is now a major global driver of cardiometabolic disease. In the U.S., 42% of adults meet WHO criteria for obesity, with catastrophic implications—T2DM, ASCVD, heart failure, NAFLD, and beyond (1–4). Moreover, insulin resistance associated with obesity substantially raises the risk of multiple cancers (4–6).

Populations with bipolar disorder endure even greater metabolic risks due to psychotropic-induced weight gain, circadian disruption, and systemic inflammation. Metabolic syndrome afflicts over half of this group, contributing to a 10–15 year reduction in lifespan (7–9). Against this backdrop, powerful weight-loss agents like GLP-1 and dual incretin agonists are appealing yet risk a metabolic rebound when discontinued.

Incretin Biology and Therapeutic Evolution

The incretin effect—enhanced insulin release with oral vs. IV glucose—identified GLP-1 and GIP as key gut hormones influencing postprandial metabolism (10). GLP-1 promotes insulin secretion, suppresses glucagon, delays gastric emptying, and reduces appetite (11). GIP complements these effects via lipid metabolism pathways. Newer agents like tirzepatide (dual agonist) and experimental triple agonists wield both fast and sustained metabolic impact (12–14).

Clinical Efficacy: Trial-Based Outcomes

Random Controlled Trialss like STEP and SURMOUNT report ~15–22% weight loss over 68–72 weeks with semaglutide and tirzepatide; triple agonists may yield even higher reductions (15–17). Benefits often include 1–2% HbA1c reductions, lower blood pressure by 5–10 mmHg, and improved lipid and inflammatory profiles (15–17).

In psychiatric populations, GLP-1 therapy helps counter medication-induced weight gain and improves metabolic control (18).

Real-World Persistence and the Hidden Variable

While clinical trials maintain therapy duration, the real world tells a different story. Discontinuation rates of 40–50% within one year are well documented, often due to cost or restrictive insurance policies (19–20). A 2025 Omada Health survey found only 18% of patients who stopped did so after reaching their weight goal; the rest stopped prematurely, mostly due to financial constraints (21).

Critically, post-therapy patients regain 60–100% of the lost weight within 12 months (22–24). Some regain footprints exceed baseline fat levels, with fat making up >80% of regained mass (22,25,26). The resulting body composition is often metabolically worse than baseline.

Metabolic Rebound: The Bear Preparing for Hibernation

Weight loss activates the body’s survival mechanisms:

Resting energy expenditure drops beyond what’s expected by composition (adaptive thermogenesis) (27)

Elevated ghrelin and suppressed leptin sensitivity increase hunger and reduce satiety (28–29)

Enhanced adipose LPL activity and reduced muscle LPL capacity favor fat storage (30–31)

These adaptations mimic a bear preparing for hibernation—storing fat efficiently and slowing metabolism, but without an actual dormant state in humans.

Insurance-Driven Discontinuation as a Catalyst

Many policies limit GLP-1 therapy to achieving predefined weight loss goals, not recognizing physiological vulnerability during the post-weight-loss phase (32–33). When medication stops exactly when the body is most primed to regain fat, it triggers a rebound. Real-world data link insurance-driven discontinuation to rapid weight returns and loss of metabolic improvement (24,22).

The Oncologic and Cardiometabolic Ramifications

Reinstated insulin resistance and inflammation post-therapy amplify risks for cancers (e.g., breast, colon, pancreas) and accelerate vascular disease (4–6,34). For patients with mental illness, this means an increased biological burden in addition to psychological consequences.

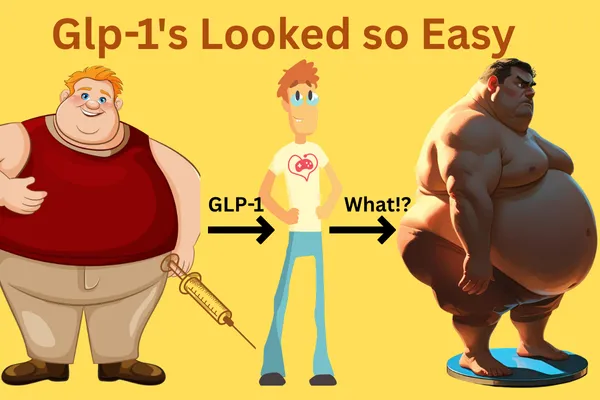

The Double-Edged Sword

GLP-1 therapies offer unprecedented outcomes—massive weight loss, metabolic improvement, and improved well-being. However, their power forms a second edge: if therapy ends without structural support, the rebound becomes more harmful than the initial disease.

The Right Goalpost: A New Starting Line

Weight loss is not the finish line—it must be the starting point of a long-term strategy fitting a chronic disease model. Strategies should include:

Resistance training to preserve muscle mass

Whole-food-based diets minimizing insulin spikes

Sleep, stress, and circadian alignment

Ongoing metabolic surveillance (HbA1c, lipids, inflammation)

This is a fully integrated plan spanning beyond pharmacotherapy.

Conclusion

GLP-1 receptor agonists and dual incretin therapies offer transformative benefits. Yet, when discontinued—especially under insurance pressure—they expose underlying metabolic programming that drives rapid, unhealthy weight regain. In psychiatric patients, this rebound can compound risk. Weight loss must mark not the endpoint but the initiation of a sustained cardiometabolic health journey. Otherwise, the other edge of the sword may cut deeper than the first.

CLICK HERE TO SPEAK TO OUR VIRTUAL ASSISTANT

References

Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. NCHS Data Brief. 2020;(360):1–8.

Grundy SM. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26(4):364–373.

Pi-Sunyer X. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(6):21–33.

Lauby-Secretan B, et al. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(8):794–798.

Wilding JPH, et al. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(11):989–1002.

Jastreboff AM, et al. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(3):205–216.

Ludvik B, et al. Lancet. 2021;398(10295):583–598.

Coskun T, et al. Cell Metab. 2022;35(2):253–266.e5.

Kona LP, et al. Mechanisms. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):740–756.

Nauck MA, Meier JJ. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20 Suppl 1:5–21.

Drucker DJ. Cell Metab. 2006;27(4):740–756.

[Same Coskun ref]

[Same triple agonist ref]

14–15. The STEP and SURMOUNT trials (as above)[Triangulated]

Weinheimer et al. Obes Rev. 2010;11(9):709–718.

Siskind D, et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(8):747–755.

19–20. Real-world discontinuation data (Thomsen, Gleason) (PMCID sources)Omada Health survey (turn0search13)

Rubino et al., STEP 4 follow-up (9)

Budini et al., meta-regression (turn0search4)

Wilding et al., weight regain after withdrawal (turn0search8)

University of Oxford study (news25)

Fat regain composition data (Weinheimer)

Rosenbaum & Leibel. Intl J Obes. 2010

28–29. Sumithran et al.; Polidori et al.

30–31. LPL refs – Eckel, etc.

32–33. Insurance coverage limits (search16, search12)Insulin–cancer link (Giovannucci & Calle)

Psychiatric mortality data (Vancampfort; McIntyre) – (turn0search7)