The M-Quad: Where Metabolism Meets the Heart

The M-Quad: A Unifying Cardiometabolic Framework Linking Insulin Resistance, Cortisol Dysregulation, Hypertension, and HFpEF

John Sciales, M.D.

CardioCore Metabolic Wellness Center

“Getting to the Core… The Path to Wellness — Where Being Healthy Is Not an Accident.”

Acknowledgments

The author gratefully acknowledges the mentorship, insight, and pioneering contributions of Dr. Robert Eckel, Dr. Christie Ballantyne, and the late Dr. George Bakris, whose foundational work in cardiometabolic medicine continues to shape modern understanding of metabolism, cardiovascular risk, and prevention.

Special appreciation is also extended to colleagues and thought leaders including Dr. Deepak Bhatt, Dr. Paul Ridker, Dr. Anne Peters, Dr. Keith Ferdinand and the many investigators and clinicians of the Cardiometabolic Health Congress, whose collective dedication to advancing metabolic and cardiovascular integration has provided both the inspiration and the intellectual framework upon which this manuscript was built. Their contributions remind us that medicine advances not through isolated discoveries but through shared vision — a commitment to see disease not as fragments, but as a unified terrain to be understood, healed, and prevented together.

Article Roadmap: Understanding the M-Quad

This article is intended for physicians and clinicians involved in the care of complex cardiovascular and cardiometabolic conditions. Although it appears here in a public forum, it is not written for the layperson. That said, individuals living with advanced cardiometabolic issues may still find its explanations accessible and informative.

Each section can be read independently, yet together they form a coherent, upstream strategy for prevention and treatment. The purpose of this work is to reframe cardiovascular disease through the lens of metabolic dysfunction, to move beyond downstream symptom management and toward understanding and addressing the upstream forces that drive hypertension, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, and cortisol-related cardiovascular stress.

By bridging the gap between cardiology, endocrinology, and functional metabolic medicine, this article aims to guide physicians toward more integrated, mechanism-based care, where prevention and treatment are aligned at the core.

Summary

Modern cardiometabolic care remains fragmented and compartmentalized—hypertension, dyslipidemia, heart failure, and metabolic syndrome are managed as distinct disease states. Yet they share a common upstream terrain: insulin resistance, maladaptive cortisol physiology, hemodynamic pressure, and myocardial remodeling. Hypertension is treated as a hemodynamic disorder. Cortisol and stress are often dismissed as “soft” factors. HFpEF is addressed after irreversible myocardial remodeling has occurred. And insulin resistance, despite being the earliest and most modifiable factor, is frequently overlooked unless hyperglycemia is present.

This compartmentalized approach stands in sharp contrast to the growing recognition that these conditions are deeply intertwined. Insulin resistance sits at their core, with maladaptive cortisol responses amplifying vascular and metabolic injury, hypertension expressing the vascular consequences, and HFpEF emerging as the myocardial endpoint.

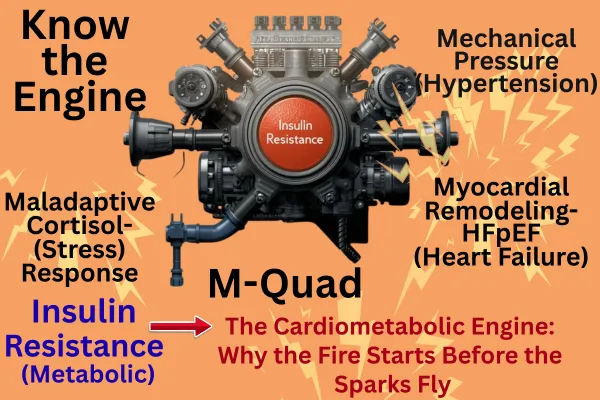

We introduce the M-Quad—a conceptual framework linking the four M’s

Metabolism (insulin resistance and energy inflexibility)

Maladaptive cortisol response (HPA axis dysregulation)

Mechanical pressure (hypertension as vascular expression)

Myocardial remodeling (HFpEF as end-organ phenotype)

This axis should be viewed as a single integrated process, just as chronic kidney disease, diabetes, and heart failure are now recognized as the cardiorenal–metabolic syndrome.

Methods: Review of mechanistic literature, clinical observations, and cardiometabolic physiology to synthesize the four axes into an integrated model.

Findings: IR precedes diabetes by decades, drives hypertension (especially resistant hypertension), fuels cortisol dysregulation, and promotes structural heart changes leading to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Cortisol amplifies this loop via sympathetic and RAAS activation. Myocardial remodeling reflects chronic metabolic starvation and maladaptive energy signaling.

Conclusion: Addressing this system through NESS (Nutrition, Exercise, Sleep, Spirituality/Socialization) and targeted metabolic pharmacology represents a paradigm shift in cardiovascular prevention and treatment, moving from chasing downstream numbers to extinguishing the upstream fire.

Outline

Section Summaries

1. Introduction: Why the M-Quad Matters Modern cardiovascular management targets numbers; blood pressure, LDL, glucose, while neglecting the upstream metabolic and neurohormonal terrain. This opening section reframes cardiovascular disease as a systemic metabolic disorder and introduces the M-Quad as a cohesive pathophysiologic model.

2. Metabolism: Insulin Resistance as the Engine Explores insulin resistance as the earliest, most modifiable driver of cardiometabolic disease. Describes its inflammatory, endocrine, endothelial, and mitochondrial effects, the evolutionary mismatch of caloric excess, and the need for early physiologic detection beyond glycemia.

3. Maladaptive Cortisol Response: The Stress Amplifier Defines medical stress as any condition activating the sympathetic nervous system and elevating cortisol. Chronic HPA axis stimulation creates a self-perpetuating cortisol–insulin loop that raises blood pressure, drives inflammation, and accelerates myocardial and vascular injury.

4. Mechanical Pressure: Hypertension as the Vascular Manifestation Positions hypertension, particularly resistant hypertension, as a downstream expression of metabolic and hormonal dysregulation rather than an isolated hemodynamic disorder. Enumerates the renal, vascular, and neurohormonal mechanisms linking insulin resistance and hypertension.

5. Myocardial Remodeling and Energetic Failure: HFpEF as End-Organ Syndrome Redefines heart failure with preserved ejection fraction as a metabolic and inflammatory phenotype characterized by impaired substrate flexibility, endothelial inflammation, and diastolic stiffness. Explains how energy starvation, cortisol biology, and hypertension converge on the myocardium.

6. The M-Quad: A Single Axis, Not Four Diseases Integrates metabolism, cortisol, pressure, and remodeling into one axis of disease. Argues that cardiometabolic specialists must lead early, upstream intervention before fragmentation into subspecialty clinics occurs. The M-Quad becomes the foundation of modern cardiometabolic medicine.

7. Therapeutic Landscape: Targeting Insulin Resistance and Protecting the Terrain Outlines both non-pharmacologic (NESS: Nutrition, Exercise, Sleep, Socialization/Spirituality) and pharmacologic interventions that restore terrain health. Contrasts insulin-sensitizing and terrainsupportive drugs (GLP-1 RA, SGLT2i, PPAR-γ agonists, bromocriptine) with agents that worsen the terrain (sulfonylureas, excessive exogenous insulin, high-dose statins). Includes summary tables rating each class ( helpful ◯ neutral harmful).

8. Future Directions and Conclusion: Redefining Cardiometabolic Medicine Calls for early terrain mapping, integration of IR and cortisol screening into all chronic-disease care, and research on upstream therapies combining NESS and precision pharmacology. Concludes that to heal the heart, we must first restore metabolism and correct the terrain.

Section 1 — Introduction: Why the M-Quad Matters

Despite unprecedented progress in cardiovascular pharmacotherapy and device-based interventions, the global prevalence of hypertension—including resistant hypertension, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), and metabolic cardiovascular disease continues to rise (1–3). Traditional management remains fragmented, each disorder treated as a discrete entity rather than as the expression of a shared upstream pathophysiology. Hypertension is conceptualized primarily as a hemodynamic disturbance; dyslipidemia as a lipid imbalance; and HFpEF as a mechanical problem of the heart. Yet converging evidence from molecular biology, endocrinology, and clinical epidemiology demonstrates that these syndromes share a common terrain, rooted in insulin resistance, maladaptive neurohormonal activation, vascular stiffening, and energetic failure (4–8).

From Downstream Numbers to Upstream Mechanisms

Modern cardiology has been extraordinarily successful at lowering blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, and hemoglobin A1c. However, the persistence, and in many regions acceleration, of cardiometabolic morbidity reveals a paradox: controlling downstream metrics does not necessarily restore metabolic homeostasis (9, 10). The clinical gaze has remained fixed on the measurable outputs, pressure, glucose, cholesterol, while neglecting the integrated metabolic and neurohormonal networks that drive them. In effect, we have been treating sparks while the fire rages. Without extinguishing the fire, the metabolic and inflammatory terrain, those sparks will continue to ignite new disease.

Introducing the M-Quad

The M-Quad framework proposes that the dominant axis of modern cardiovascular disease consists of four interdependent domains:

Metabolism: Insulin resistance and impaired metabolic flexibility constitute the initiating defect, altering substrate preference, endothelial signaling, and mitochondrial efficiency.

Maladaptive Cortisol Response: Chronic hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis activation amplifies sympathetic drive, renin–angiotensin–aldosterone (RAAS) tone, and visceral adiposity.

Mechanical Pressure: Sustained hemodynamic load emerges as the vascular manifestation of metabolic and neurohormonal injury, culminating in hypertension, especially resistant hypertension—as the overt expression of this process.Just as hyperglycemia represents the late metabolic expression of insulin resistance, resistant hypertension reflects the vascular end-stage of the same upstream dysfunction.

Myocardial Remodeling: Prolonged metabolic and mechanical stress yield energetic starvation, interstitial fibrosis, and the HFpEF phenotype.

Each “M” feeds the next, forming a continuous feed-forward loop rather than isolated disease compartments. Insulin resistance and cortisol dysregulation ignite the cascade; vascular stiffness and pressure reinforce it; myocardial remodeling embodies its terminal expression (11–15).

Intervening at the Core

When we intervene precisely and early at the metabolic core, the effects are amplified downstream, transforming disease management into disease reversal. This represents the future of medicine: acting with precision, purpose, and personalization before the damage is done. By identifying these processes as one integrated entity and correcting the upstream terrain, rather than stacking medications to chase isolated numbers, we can make meaningful, durable differences in patient outcomes. The M-Quad framework thus calls for a reorientation of cardiology itself: from suppression to prevention, from reactivity to restoration.

A Needed Paradigm Shift

As the cardiorenal–metabolic model unified diabetes, kidney disease, and heart failure into a single continuum (16, 17), the M-Quad reframes cardiometabolic disease as a unified, dynamic process. It demands early detection of insulin resistance and stress-axis activation, metabolicprecision therapeutics, and lifestyle interventions that restore flexibility at the cellular and systemic levels. Without the fire, the sparks fade. When addressed early, the M-Quad can be reshaped, not simply managed, redirecting cardiovascular medicine toward true disease modification and longevity.

Key References

Benjamin EJ et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics—2024 Update. Circulation.2024;149:e1–e160.

Tsao CW et al. Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction in the United States.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;81:2151–2165.

Yancy CW et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022;79:e263–e421.

Reaven GM. Role of Insulin Resistance in Human Disease. Diabetes.1988;37:1595–1607.

Ferrannini E, Cusi K. Insulin Resistance and Hypertension. Clin Exp Hypertens.2022;44:467–475.

Esler M, Kaye DM. Sympathetic Nervous System Activation in Cardiometabolic Disease. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2023;81:1–12.

Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A Novel Paradigm for HFpEF: Comorbidities Drive Myocardial Dysfunction through Coronary Microvascular Endothelial Inflammation.J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:263–271.

Shah SJ et al. Phenomapping for Novel Classification of HFpEF. Circulation.2022;145:557– 572.

McMurray JJ, Packer M. The Limitations of Contemporary Cardiovascular Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2023;388:1153–1165.

Nichols GA et al. Trends in Cardiometabolic Multimorbidity, 1999–2022. JAMA.2023;330:1478–1489.

De Boer RA et al. Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and HFpEF: Mechanistic Insights. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:2943–2955.

Schlaich MP et al. Cortisol and Sympathetic Activity in Resistant Hypertension.Hypertension. 2023;81:1129–1138.

Seferović PM et al. Vascular Stiffness and Pressure Overload in HFpEF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2021;23:1097–1110.

Lopaschuk GD et al. Myocardial Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ Res.2021;128:1487–1505.

Sattar N, Packer M. Metabolic–Cardiac Continuum: From Insulin Resistance to HFpEF. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:456–472.

Vaduganathan M et al. Cardiorenal–Metabolic Disease: Unified Pathophysiologic Model. Lancet. 2023;401:1023–1038.

Packer M. The Cardiometabolic Syndrome as the New Heart Failure Frontier. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:785–797.

Section 2 — Metabolism: Insulin Resistance as the Engine

Insulin resistance (IR) is among the most pervasive yet least recognized drivers of modern chronic disease. Once viewed narrowly as a pre-diabetic metabolic anomaly, it is now understood as a systemic disorder that disrupts energy metabolism, endocrine signaling, vascular integrity, neurocognitive regulation, and inflammatory balance (1–4). It represents not merely an abnormal response to glucose but a fundamental cellular miscommunication between energy availability and energy utilization, a signal that the metabolic terrain is overloaded, inflamed, or under duress.

A State of Metabolic Miscommunication

Insulin is the body’s metabolic foreman, the hormone that decides whether energy will be stored or burned. In the ancestral environment of caloric scarcity and intermittent feeding, this system ensured survival. In today’s environment, defined by caloric excess, refined carbohydrates, sleep deprivation, chronic psychosocial stress, and physical inactivity, the same signal becomes maladaptive. Constant glycemic stimulation and near-continuous feeding maintain chronically elevated insulin levels; the receptor, persistently bombarded, becomes desensitized. The cell down-regulates receptor sensitivity in self-defense, initiating the biochemical signature of insulin resistance (5–7).

This survival circuitry is exemplified by the bear preparing for hibernation. In autumn, insulin directs the bear toward high-glycemic foods such as berries and honey, stimulating fat storage and slowing metabolism. Insulin enhances mitochondrial coupling, increasing energy efficiency—, the metabolic equivalent of achieving 50 miles per gallon. When insulin levels fall, as in fasting or starvation, the mitochondria become uncoupled, wasting energy as heat and accelerating metabolism. Thus, insulin is not simply a sugar regulator but a signal of energy abundance, shifting the organism from fuel utilization to fuel conservation.

In humans, this adaptation, once critical for survival, now collides with perpetual caloric abundance. For the first time in history, more people are obese than malnourished (8). The same biology that protected the hunter-gatherer now drives modern cardiometabolic disease.

The Hidden Duration Before Glycemia

As insulin resistance develops, glucose homeostasis remains deceptively “normal” through compensatory hyperinsulinemia. Yet the cost of this adaptation is profound: endothelial dysfunction, increased sympathetic tone, mitochondrial stress, and inflammation occur long before any rise in fasting glucose (9, 10). By the time hemoglobin A1c or plasma glucose becomes abnormal, insulin resistance has been active for one to two decades. De Fronzo and colleagues showed that well before glucose intolerance appears, renal and hepatic adaptations emerge, altered tubular thresholds for glucose reabsorption, decreased peripheral glucose uptake, and shifts in hepatic gluconeogenesis (11). Glycemia is an extremely late manifestation of an entrenched process. The reflex to equate insulin resistance with hyperglycemia obscures the earliest and most reversible, phase of cardiometabolic dysfunction.

Insulin: More Than Glucose Regulation

Insulin’s role extends far beyond GLUT-4–mediated glucose transport. It is a neurohormone and master anabolic regulator influencing multiple organ systems and molecular pathways:

Protein synthesis and cellular growth via PI3K/Akt and mTOR signaling.

Lipid storage and mobilization, deciding whether substrates are oxidized or stored.

Mitochondrial efficiency and coupling, determining energy conservation and thermogenesis.

Endothelial nitric-oxide release, regulating vascular tone and blood pressure.

Neurotransmission and mood, modulating dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate networks (12–14).

Dr. Roger McIntyre and colleagues at the University of Toronto have shown that insulin resistance is strikingly prevalent among patients with psychiatric illness, particularly major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (15–17). Their research reveals that impaired insulin signaling in the brain promotes neuroinflammation, loss of neuroplasticity, and defective glucose utilization within neural circuits. These insights explain why patients with psychiatric illness die predominantly of cardiometabolic disease, not because of isolated medication effects or lifestyle alone, but because the same metabolic pathology links the brain to the heart and the vasculature. Insulin resistance therefore represents a unified disorder of mind and metabolism, one that erodes both psychological and physiological resilience.

A Pro-Inflammatory and Neurohormonal State

Insulin resistance is not a “sugar disease.” It is a pro-inflammatory, pro-oxidative, and neurohormonal condition influencing nearly every physiologic axis:

Endocrine and Adipose Axis: Hyperinsulinemia promotes visceral adiposity, leptin resistance, and inflammatory adipokine profiles (18).

Endothelial Axis: Reduced nitric-oxide bioavailability and vascular stiffness drive hypertension, and particularly resistant hypertension, as the vascular expression of metabolic injury (19).

Autonomic and RAAS Activation: Insulin heightens sympathetic tone and aldosterone signaling (20).

Renal Axis: Enhanced tubular sodium retention and vasoconstriction elevate intravascular volume (21).

Myocardial and Mitochondrial Axis: Loss of metabolic flexibility forces reliance on fattyacid oxidation, creating the energetic starvation seen in HFpEF (22–24).

Cortisol and Stress Axis: Hyperinsulinemia stimulates the HPA axis and raises cortisol, which feeds back to worsen insulin resistance (25).

Microbiome Axis: Dysbiosis and lipopolysaccharide translocation sustain systemic inflammation (26).

A Call to Recognize the Unified Terrain

Insulin resistance is the common soil from which hypertension, hypercortisolism, psychiatric disease, and heart failure all emerge. To continue treating these as separate end-states is to mistake sparks for the fire. Cardiologists, psychiatrists, and all clinicians confronting chronic disease must learn to measure, quantify, and address insulin resistance, independent of glycemia. Only by acknowledging this shared terrain can we move from reactive disease management to proactive metabolic restoration.

We must awaken to this reality: the same biological machinery that once helped a bear survive the winter now drives the global epidemic of obesity, diabetes, depression, and cardiovascular disease. True prevention begins by restoring metabolic balance, not waging war on glucose, but understanding the orchestration of insulin itself.

The Foundational Engine of the M-Quad

Within the M-Quad framework, insulin resistance is the engine that ignites every other component, maladaptive cortisol responses, mechanical hypertension, and myocardial remodeling. It initiates the metabolic fire whose heat is felt throughout the cardiovascular and neuroendocrine systems. When we intervene early and precisely at this core, the effects are amplified downstream, transforming disease management into disease reversal.

Correcting the upstream terrain, through precision nutrition, metabolic flexibility, movement, sleep optimization, stress modulation, and targeted pharmacologic support, extinguishes the fire before the organs ignite. Only then can cardiometabolic medicine move from suppression to restoration.

Key References

Reaven GM. Role of Insulin Resistance in Human Disease. Diabetes. 1988;37:1595-1607.

Kahn SE et al. Mechanisms Linking Obesity to Insulin Resistance and Type 2 Diabetes. Nature. 2019;575:51-58.

DeFronzo RA. Pathogenesis of Insulin Resistance. Diabetes Care. 2020;43:177-189.

Cusi K. Insulin Resistance in Cardiometabolic Disease. Nat Rev Cardiol.2022;19:629-647.

Petersen MC, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance.Physiol Rev. 2018;98:2133-2223.

Czech MP. Insulin Receptor Signaling. Cell Metab. 2020;31:410-425.

Hotamisligil GS. Inflammation and Metabolic Disorders. Nature. 2006;444:860-867.

GBD Obesity Collaborators. Global Burden of Obesity 2023. Lancet.2024;403:1059-1074.

Ferrannini E. Insulin and the Endothelium. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol.2021;48:677-684.

Muniyappa R et al. Endothelial Dysfunction in Insulin Resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107:1093-1106.

DeFronzo RA. Early Renal and Metabolic Changes Preceding Hyperglycemia.Diabetes Care. 2020;43:177-189.

Kleinridders A et al. Insulin Action in the Brain. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:681-691.

Schulingkamp RJ et al. Insulin Receptors and Brain Function. Neuroscience.2000;101:1123-1134.

McNay EC, Recknagel AK. Brain Insulin Signaling and Cognition. Front Neurosci.2021;15:673-692.

McIntyre RS et al. Insulin Resistance in Major Depressive Disorder. Mol Psychiatry.2021;26:234-244.

McIntyre RS, Mansur RB. Neurobiology of Insulin Resistance in Mood Disorders. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:601-610.

McIntyre RS et al. Shared Pathophysiology Between Metabolic and Psychiatric Disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;125:110-125.

Saltiel AR, Olefsky JM. Inflammatory Mechanisms Linking Obesity and Metabolic Disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1-4.

Sowers JR. Hypertension and Insulin Resistance. Hypertension. 2022;79:1189-1200.

Hall JE et al. Renal Mechanisms in Insulin Resistance and Hypertension.Hypertension. 2019;74:1075-1083.

Lopaschuk GD et al. Myocardial Energy Metabolism in Heart Failure. Circ Res.2021;128:1487-1505.

De Boer RA et al. Insulin Resistance, Obesity, and HFpEF. Eur Heart J.2022;43:2943-2955.

Packer M. The Metabolic–Cardiac Continuum. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:456-472.

Packer M. Precision Metabolic Therapy and Cardiovascular Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:785-797.

Section 3 — Maladaptive Cortisol Response: The Stress Amplifier

Cortisol, Stress Physiology, and the Insulin-Resistance Engine

Cortisol is the body’s most potent survival hormone, indispensable in acute stress yet profoundly injurious when chronically activated. Within the M-Quad, maladaptive cortisol physiology represents the second pillar: the stress amplifier that magnifies the metabolic derangements initiated by insulin resistance.

Most current approaches to cortisol dysregulation focus narrowly on the adrenal gland, as if the problem resided in the cortex itself. But the adrenal is not the disease; it is the messenger organ responding to continuous upstream signaling from the hypothalamus, pituitary, sympathetic nervous system, and metabolic terrain. Drugs that simply suppress adrenal steroidogenesis may mute the noise but leave the orchestra of activation untouched. The M-Quad insists we look upstream, to the neuroendocrine and metabolic drivers that keep the gland in overdrive, because the root pathology lies in sustained stress signaling, not in adrenal compliance.

The Medical Definition of Stress

Medically, stress is defined as any condition that activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and elevates cortisol. Whether the initiating trigger is emotional, inflammatory, infectious, or metabolic, the physiologic result is the same: activation of the “fight-or-flight” network characterized by catecholamine release and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis stimulation. Acutely, this response is protective, an essential evolutionary mechanism for survival.

The stress response, however, was never designed for permanence. It evolved as a short-term adaptation, an emergency circuit to mobilize energy, sharpen cognition, and prepare for immediate action. When the sympathetic nervous system and HPA axis are briefly activated, as they might be when a gun is pointed at one’s head, the response is profoundly protective. Heart rate and blood pressure rise, glucose floods the bloodstream, and oxygen delivery to muscle and brain peaks. Yet this response is meant to last three minutes, not three months.

In the modern world, where threats are psychological, social, or economic rather than physical, this same circuitry is triggered repeatedly without resolution. The result is chronic sympathoadrenal activation and persistent cortisol elevation, a biologic state in which the very systems designed to ensure survival become instruments of disease. Over time, the continual release of catecholamines and glucocorticoids reshapes metabolism, elevates blood pressure, stiffens arteries, and sustains insulin resistance. The protective becomes pathogenic; the emergency becomes the environment.

From Acute Response to Chronic Dysregulation

Sympathetic activation releases catecholamines that elevate heart rate, contractility, and blood pressure.

HPA-axis activation follows within minutes: CRH and ACTH stimulate adrenal cortisol secretion.

In the healthy organism, feedback inhibition curtails the response. Under chronic psychosocial, inflammatory, or metabolic stress, this feedback loop erodes. The off-switch fails, and cortisol remains persistently elevated—converting an emergency mechanism into a continuous injury signal.

Chronic Stress → Cortisol Elevation → Insulin Resistance

Persistent cortisol elevation produces far-reaching metabolic distortion:

↑ Hepatic gluconeogenesis → increased insulin demand.

↑ Visceral adiposity → inflammatory cytokine production.

↓ Skeletal-muscle mass → reduced glucose disposal.

↑ Adrenergic and RAAS sensitivity → hypertension and sodium retention.

↓ Endothelial nitric oxide → vascular stiffness and impaired flow.

Over time, these changes converge into the hemodynamic and structural hallmarks of resistant hypertension and HFpEF.

Insulin Resistance → Cortisol Amplification

The relationship is reciprocal. Hyperinsulinemia stimulates ACTH and adrenal cortisol release, while inflammatory cytokines upregulate 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1), regenerating cortisol locally within adipose and vascular tissue. The result is a feedforward loop:

Cortisol drives insulin resistance; insulin resistance drives cortisol.

Sustained ACTH signaling and hyperinsulinemic adrenal sensitization produce functional bilateral adrenal hyperplasia, a morphologic echo of chronic upstream overdrive. The gland enlarges because the brain keeps shouting.

Hemodynamic and Structural Consequences

Persistent adrenergic vasoconstriction

Sodium retention and plasma-volume expansion

Myocardial fibrosis and diastolic stiffness

Microvascular rarefaction and mitochondrial exhaustion

These are not isolated outcomes but downstream expressions of a single neuro-metabolic conversation gone awry.

Beyond Glycemia: The Cortisol–Insulin Axis

Cortisol’s Actions Insulin’s Response

↑ Gluconeogenesis → ↑ Insulin load Hyperinsulinemia → ↑ ACTH and adrenal cortisol ↑ Visceral adiposity, ↓ muscle Inflammation → ↑ 11β-HSD1 → ↑ local cortisol ↑ Sympathetic tone, RAAS activity ↑ Sodium retention, vascular stiffness

This bi-directional endocrine engine drives vascular remodeling and myocardial energetics more powerfully than late-stage hemodynamic factors. Treating cortisol excess without addressing its metabolic ignition is like mopping the floor while the pipe still leaks.

Clinical Implications and the M-Quad Perspective

The persistence of maladaptive cortisol physiology illustrates why the M-Quad was created. The problem is not the adrenal gland,it is the chronic upstream activationgenerated by insulin resistance, inflammation, and unremitting sympathetic tone. True correction requires calming the terrain: restoring metabolic flexibility, regulating sleep and circadian rhythm, reducing inflammatory load, and rebuilding autonomic balance through movement, social connection, and mindfulness.

Only by addressing the upstream circuitry can we silence the downstream noise. When the fire cools, the smoke clears,the gland quiets itself.

Key References

Chrousos GP, Gold PW. The Concepts of Stress and Stress System Disorders.JAMA. 1992;267:1244-1252.

Sapolsky RM et al. How Do Glucocorticoids Influence Stress Responses? Endocr Rev. 2000;21:55-89.

McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central Role of the Brain in Stress and Adaptation. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1216-1223.

Walker BR. 11β-HSD1 in Metabolic Disease. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:312-330.

Joseph JJ, Golden SH. Cortisol Dysregulation: The Missing Link Between Stress and Cardiometabolic Disease? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1861-1870.

Bremmer MA et al. Adrenal Volume and Metabolic Syndrome: Correlation With Insulin and CRP. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:E1033-E1040.

Sudo N et al. Chronic Stress Induces Adrenal Hyperplasia and Insulin Resistance in Rodents. Endocrinology. 2015;156:1653-1664.

Packer M. Precision Metabolic Therapy and Cardiovascular Prevention. N Engl J Med. 2024;390:785-797.

Section 4 — Mechanical Pressure: Hypertension as the Vascular Expression of Metabolic Stress

The Forgotten Root

Hypertension is not a random rise in arterial pressure; it is the vascular expression of a deeper metabolic disorder. The vast majority of patients with resistant hypertension once had “essential” hypertension, and most of those began decades earlier with insulin resistance (IR). In truth, hypertension often represents the earliest measurable manifestation of IR, long before dysglycemia appears (1–4).

Ferrannini and Reaven independently demonstrated that essential hypertension exists within an insulin-resistant milieu, even in lean nondiabetic individuals (1, 2). Cohort data such as the Kuopio and ARIC studies further confirmed that fasting insulin and HOMA-IR independently predict the onset of hypertension (3, 4). Thus, IR is not an epiphenomenon but the engine itself.

The Insulin–Cortisol–Sympathetic Triad

Insulin resistance, maladaptive cortisol activation, and chronic sympathetic tone form a selfreinforcing triad that transforms metabolic flexibility into vascular rigidity. Hyperinsulinemia activates both the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS); cortisol amplifies these effects through glucocorticoid-induced adrenergic sensitization and visceral adiposity (5, 6). The triad sustains sodium retention, vascular constriction, endothelial injury, and myocardial remodeling, the pathophysiologic substrate of resistant hypertension.

When clinicians treat only the pressure, they treat the spark while ignoring the fire.

A. Renal and Volume Regulatory Mechanisms

Insulin-stimulated proximal-tubular Na⁺ reabsorption via Na⁺/H⁺ exchange expands plasma volume and raises blood pressure (7).

Non-renal vascular Na⁺ accumulation increases intracellular Ca²⁺ and enhances vasoconstriction (8).

Impaired natriuretic-peptide signaling: obesity and IR up-regulate NPR-C in adipose tissue, blunting natriuresis and vasodilation (9, 10).

Obesity-related hemodynamic load: increased circulating volume and stroke volume elevate preload and afterload (11).

Glomerular hyperfiltration from chronic IR leads to RAAS activation (12).

Medullary hypoxia from Na⁺ retention fosters interstitial fibrosis (13).

B. Neurohormonal and Autonomic Mechanisms

Central sympathetic activation by hyperinsulinemia elevates systemic vascular resistance and heart rate (14).

Selective leptin resistance maintains leptin’s sympatho-excitatory action despite satiety failure (15).

Obstructive sleep apnea, via intermittent hypoxia, triggers SNS and RAAS surges (16).

Heightened pressor reactivity to catecholamines and angiotensin II in IR states (17).

Reduced baroreflex sensitivity increases BP variability and loss of nocturnal dipping (18).

Chronic diuretic-induced volume depletion activates baroreceptors and renin release, heightening SNS tone and cortisol, thereby perpetuating IR and resistant hypertension (19, 20).

C. Endothelial and Vascular Structural Mechanisms

Selective PI3K/Akt impairment decreases nitric-oxide bioavailability, favoring vasoconstriction (21).

Endothelial glycocalyx degradation from oxidative and glycative stress blunts shear mediated dilation (22).

VSMC proliferation and collagen deposition through MAPK/ERK activation increase arterial stiffness (23).

Microvascular rarefaction reduces capillary density and raises total peripheral resistance (24).

AGE cross-linking stiffens the vascular matrix even before overt hyperglycemia (25).

Endothelial insulin-receptor down-regulation under chronic hyperinsulinemia impairs vasodilatory signaling (26, 27).

Capillary basement-membrane thickening restricts nitric-oxide diffusion (28).

D. Endocrine and RAAS Pathways

Aldosterone overproduction: insulin directly stimulates zona-glomerulosa cells (29).

Adipose-tissue RAAS activation amplifies systemic vasoconstriction (30).

Cortisol–SNS feedback mutually reinforces vasoconstriction and volume retention (31). Adrenal hyperplasia driven by chronic

ACTH and insulin signaling sustains aldosterone excess (32).

Blunted natriuretic-peptide release from pericardial and adipose constraint, coupled with NP-clearance receptor up-regulation (33, 34).

E. Inflammatory and Adipokine Mechanisms

Pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-6, resistin) impair NO signaling and stimulate RAAS and SNS (35).

Low adiponectin / high resistin ratios elevate vasomotor tone (36).

Chronic oxidative stress increases endothelin-1, a potent vasoconstrictor (37).

Gut-derived endotoxemia (LPS) activates TLR-4–mediated vasoconstrictive inflammation (38).

Perivascular-adipose inflammation generates ROS and increases vascular stiffness (39, 40).

CKD-associated inflammation elevates FGF-23 and sympathetic drive (41).

F. Metabolic and Cellular Energy Mechanisms

Mitochondrial inefficiency in IR shifts fuel toward fatty-acid oxidation, increasing ROS (42).

Hyperuricemia induces endothelial oxidative stress and RAAS activation (43).

Insulin-mediated VSMC hypertrophy narrows resistance vessels (23).

Impaired fuel flexibility and ketone suppression maintain a high-tone oxidative state (44).

Endoplasmic-reticulum stress disrupts vascular insulin signaling (45).

G. Gut–Microbiome Axis

IR-driven dysbiosis lowers SCFA production, diminishing GPR41/43 and vagal signaling, thereby increasing BP (46, 47).

Reduced SCFAs worsen IR and endothelial dysfunction, raising renin and RAAS activity (48, 49).

Trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) from microbial metabolism induces endothelial oxidative injury (50).

Gut-barrier disruption increases systemic LPS and vascular inflammation (51).

H. Renal–Cardiometabolic Interface and Downstream Sequelae

Chronic loop or thiazide diuretics deplete intravascular volume, activating renin, SNS, and cortisol (19, 20).

Over-diuresis and renal hypoperfusion precipitate ischemic nephropathy and CKD, perpetuating IR and inflammation (41, 52).

Reduced insulin clearance in CKD aggravates hyperinsulinemia (53).

Uremic toxins impair endothelial insulin signaling and NO bioavailability (54).

RAAS blockade without metabolic correction provides partial hemodynamic relief but fails to reverse terrain (55).

The Feedback Trap

Each pathway amplifies the next: hyperinsulinemia → SNS/RAAS activation → cortisol ↑ → endothelial damage → worsened IR.

Chronic diuretic therapy contracts plasma volume, stimulating renin and ACTH, raising cortisol, and worsening IR, a metabolic paradox that sustains hypertension and accelerates CKD.

Resistant hypertension is not therapeutic failure; it is diagnostic blindness. The more we escalate antihypertensives, the more we ignore the upstream metabolic fire.

Breaking the Loop

Even the OGTT with insulin response, though most physiologic, may miss subtle IR when β-cell compensation persists. Thus anthropometrics (waist-to-hip ratio > 0.9 men / > 0.85 women) and TG / HDL ratio remain indispensable. Yet, as Einstein observed, “Not everything that can be measured is important, and not everything that is important can be measured.”

Medicine’s obsession with quantifiable metrics blinds us to invisible physiology. True precision medicine requires both detective and architect, detective to uncover hidden metabolic chaos, architect to rebuild normal signaling before irreversible damage.

Early, targeted correction of insulin resistance — through nutritional recalibration, stress modulation, GLP-1 RAs, SGLT2 inhibitors, pioglitazone, bromocriptine, aldosterone antagonists, and microbiome restoration—restores physiologic dialogue between metabolism and vasculature. When we act upstream, we need fewer drugs downstream. Resistant hypertension is often the first clinical smoke of a metabolic inferno. Fix the terrain, and the pressure fades.

Key References

Ferrannini E, Buzzigoli G, Bonadonna R, et al. Insulin resistance in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1987;5(Suppl 5):S121–S126.

Reaven GM. Insulin resistance, hyperinsulinemia, and hypertriglyceridemia in hypertension. Hypertension. 1991;19(1 Suppl):I45–I46.

Hall JE, do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Wang Z, Hall ME. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116(6):991–1006.

Ferrannini E, Natali A. Essential hypertension, metabolic disorders, and insulin resistance. Am Heart J. 1991;121(4 Pt 2):1274–1282.

Esler M, Lambert G, Brunner-La Rocca HP, et al. Sympathetic nerve biology in essential hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28(12):986–989.

Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factorα: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87–91.

DeFronzo RA, Cooke CR, Andres R, Faloona GR, Davis PJ. Effect of insulin on renal handling of sodium, potassium, calcium, and phosphate in man. J Clin Invest. 1975;55(4):845–855.

Titze J, Machnik A. Sodium sensing in the interstitium and relationship to hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2010;19(4):385–392.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, et al. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation. 2004;109(5):594–600.

Das SR, Drazner MH, Dries DL, et al. Impact of body mass and composition on circulating levels of natriuretic peptides: results from the Dallas Heart Study.Circulation. 2005;112(14):2163–2168.

Messerli FH, Ventura HO, Frohlich ED. Cardiovascular effects of obesity and hypertension. Lancet. 1982;1(8282):1165–1168.

Hall JE, Brands MW, Henegar JR. Mechanisms of hypertension and kidney disease in obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:91–107.

Cowley AW Jr, Roman RJ. The role of the renal medulla in volume control, hypertension, and hypotension. Am J Med Sci. 1996;311(2):91–101.

Anderson EA, Hoffman RP, Balon TW, Sinkey CA, Mark AL. Hyperinsulinemia produces both sympathetic neural activation and vasodilation in normal humans. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(6):2246–2252.

Mark AL, Correia ML, Rahmouni K, Haynes WG. Selective leptin resistance: a new concept in leptin physiology with cardiovascular implications. J Hypertens. 2002;20(7):1245–1250.

Logan AG, Perlikowski SM, Mente A, et al. High prevalence of unrecognized sleep apnoea in drug-resistant hypertension. J Hypertens. 2001;19(12):2271–2277.

Brands MW, Hildebrandt DA, Mizelle HL, Hall JE. Sustained hyperinsulinemia increases arterial pressure in conscious rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260(3 Pt 2):R764–R768.

Grassi G, Cattaneo BM, Seravalle G, et al. Sympathetic activation in obese normotensive subjects. Hypertension. 1995;25(4 Pt 1):560–563.

Cowley AW Jr, Skelton MM, Pfeffer JM. Reflex control of the renal circulation during volume depletion. Clin Sci (Lond). 1982;62(4):385–391.

Grassi G, Seravalle G, Brambilla G, et al. Sympathetic activation by diuretics in human hypertension. Hypertension. 2008;52(3):381–386.

Laakso M, Edelman SV, Brechtel G, Baron AD. Decreased effect of insulin to stimulate skeletal muscle blood flow in obese man. J Clin Invest. 1990;85(6):1844–1852.

Nieuwdorp M, Meuwese MC, Vink H, Hoekstra JB, Kastelein JJ, Stroes ES. The endothelial glycocalyx: a potential barrier between health and vascular disease.Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16(5):507–511.

Muniyappa R, Montagnani M, Koh KK, Quon MJ. Cardiovascular actions of insulin.Endocr Rev. 2007;28(5):463–491.

Antonios TF, Rattray FM, Singer DR, Markandu ND, Mortimer PS, MacGregor GA. Rarefaction of skin capillaries in essential hypertension. J Hypertens. 1999;17(4):557–563.

Brownlee M. Advanced protein glycosylation in diabetes and aging. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:223–234.

Jiang ZY, Lin YW, Cheng K, et al. Insulin signaling through PI3-kinase and Akt in endothelial cells is impaired by high glucose. Diabetologia. 1999;42(4):401–409.

Kubota T, Kubota N, Moroi M, et al. Insulin receptor substrate-2 deficiency and endothelial dysfunction in mice. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(9):1373–1381.

Rizzoni D, Porteri E, Boari GE, et al. Structural alterations in subcutaneous small resistance arteries of normotensive and hypertensive patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2001;103(9):1238–1244.

Goodfriend TL, Ball DL, Egan BM, Campbell WB, Nithipatikom K. Plasma aldosterone, plasma lipoproteins, obesity, and insulin resistance in humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995;52(3–4):213–217.

Engeli S, Schling P, Gorzelniak K, et al. The adipose-tissue renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system: role in the metabolic syndrome? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85(5):1999–2004.

Esler M, Lambert E, Jennings G. Sympathetic nervous system and insulin resistance: an interdependent relationship? Diabetologia. 2008;51(5):857–864.

Schirpenbach C, Reincke M. Primary aldosteronism: current knowledge and controversies in Conn’s syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2006;2(4):220–227.

Das SR, Drazner MH, Dries DL, et al. Obesity and circulating natriuretic peptide levels: the Dallas Heart Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(11):1815–1820.

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Keyes MJ, et al. Relations of natriuretic peptides to obesity and metabolic traits. Hypertension. 2009;53(4):577–584.

Hotamisligil GS, Shargill NS, Spiegelman BM. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factorα: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259(5091):87–91.

Frühbeck G. Intracellular signalling pathways activated by leptin. Biochem J. 2006;393(Pt 1):7–20.

Kohan DE, Rossi NF, Inscho EW, Pollock DM. Regulation of blood pressure and salt homeostasis by endothelin. Physiol Rev. 2011;91(1):1–77.

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–1772.

Guzik TJ, Olszanecki R, Sadowski J, et al. Perivascular adipose tissue as a source of reactive oxygen species in the vasculature. Circulation. 2009;119(12):1661–1670.

Szasz T, Webb RC. Perivascular adipose tissue: more than just structural support. Hypertension. 2010;56(2):110–116.

Kovesdy CP, St Peter WL, Shlipak MG, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the metabolic syndrome: mechanisms and consequences. Kidney Int Suppl. 2007;(106):S10–S14.

Shulman GI. Cellular mechanisms of insulin resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(2):171–176.

Mazzali M, Hughes J, Kim YG, et al. Elevated uric acid increases blood pressure in the rat by a novel crystal-independent mechanism. Hypertension. 2001;38(5):1101–1106.

Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of insulin action and insulin resistance. Physiol Rev. 2018;98(4):2133–2223.

Ozcan U, Cao Q, Yilmaz E, et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress links obesity, insulin action, and type 2 diabetes. Science. 2004;306(5695):457–461.

Pluznick JL. Microbial short-chain fatty acids and blood pressure regulation. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2017;19(4):25. P

luznick JL, Protzko RJ, Gevorgyan H, et al. Olfactory receptor responding to gut microbiota-derived SCFAs modulates blood pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(11):4410–4415.

Marques FZ, Nelson E, Chu PY, et al. High-fiber diet and acetate supplementation change the gut microbiota and prevent the development of hypertension. Circulation. 2017;135(10):964–977.

Canfora EE, Jocken JW, Blaak EE. Short-chain fatty acids in control of body weight and insulin sensitivity. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015;11(10):577–591.

Tang WHW, Wang Z, Levison BS, et al. Intestinal microbial metabolism of phosphatidylcholine and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(17):1575–1584.

Cani PD, Amar J, Iglesias MA, et al. Metabolic endotoxemia initiates obesity and insulin resistance. Diabetes. 2007;56(7):1761–1772.

Go AS, Chertow GM, Fan D, McCulloch CE, Hsu CY. Chronic kidney disease and risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305.

Fliser D, Pacini G, Engelleiter R, et al. Insulin resistance and hyperinsulinemia are already present in patients with mild renal impairment. Kidney Int. 1997;51(1):190–197.

Stenvinkel P, Carrero JJ, Axelsson J, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20(12):2522–2526.

Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morbey C, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386(10008):2059–2068.

Section 5 — Myocardial Remodeling and Energetic Failure: Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction as the End-Organ Syndrome

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) represents the downstream myocardial manifestation of the M-Quad axis, metabolism, maladaptive cortisol response, mechanical pressure, and myocardial remodeling. It is not simply “diastolic heart failure,” but the terminal expression of a chronically energy-starved, inflamed, insulin-resistant terrain. In both HFpEF and selected non-ischemic heart-failure–with-reduced-ejection-fraction (HFrEF) phenotypes, the unifying disturbance is metabolic inflexibility, the inability of the heart to efficiently switch between glucose, fatty acids, and ketones for ATP generation (1–4). When upstream metabolic injury is unrecognized, downstream therapies remain palliative rather than curative. The prevailing focus on ejection-fraction phenotype must yield to a precision focus on genotype-level drivers: mitochondrial energetics, insulin-signaling defects, and inflammatory stress biology.

A. Metabolic Core: Insulin Resistance and Fuel Inflexibility in the Heart

Insulin resistance (IR) precedes overt diabetes by decades and is highly prevalent among patients with HFpEF, even in the absence of hyperglycemia (4–6). In the healthy heart, substrate utilization alternates flexibly between glucose and fatty acids according to energy demand and oxygen availability. In IR, this adaptive switching collapses. Glucose uptake through GLUT-4 is impaired; hyperinsulinemia inhibits hepatic ketogenesis; and the myocardium becomes forced to oxidize fatty acids exclusively, an oxygen-intensive and inefficient process that increases mitochondrial reactive-oxygen-species (ROS) production and depletes ATP reserve (5–8).

Unable to access ketones or glucose efficiently, the body increases protein catabolismto supply gluconeogenic amino acids, worsening sarcopenia and further diminishing insulin sensitivity (9). Hyperinsulinemia also activates the MAPK/ERK mitogenic limb of insulin signaling, stimulating fibroblast proliferation and collagen deposition that promote concentric remodeling and diastolic stiffness (6–8).

Pharmacologic contributors amplify this metabolic injury. Statin therapy, reflexively prescribed, depletes coenzyme Q10 (ubiquinone)—a critical electron-carrier in the mitochondrial respiratory chain, further compromising oxidative phosphorylation (10, 11). Likewise, metformin, though cardioprotective in diabetics, directly inhibits mitochondrial complex I, suppressing hepatic gluconeogenesis but also diminishing mitochondrial glucose oxidation (12, 13). In susceptible HFpEF patients, the combination of hyperinsulinemia, CoQ10 depletion, and metformin-induced mitochondrial inhibition creates a bioenergetic choke point that manifests clinically as fatigue, exercise intolerance, and impaired lusitropy.

B. Microvascular–Endothelial Axis: The NO–cGMP–PKG Brake Fails

Systemic inflammation from IR, visceral adiposity, and cortisol excess induces endothelial inflammation and capillary rarefaction within the coronary microcirculation (14–16). Loss of nitric-oxide bioavailability and reduced cyclic-GMP–protein-kinase-G signaling cause titin hypophosphorylation, cardiomyocyte stiffening, and elevated left-ventricular (LV) filling pressures despite preserved systolic function (1, 14). The glycocalyx, a shear-sensing endothelial barrier, undergoes oxidative and glycative injury, further impairing vasodilatory reserve (15, 16). These processes render the myocardium stiff, energetically starved, and pressure-intolerant.

C. Hemodynamic Load Meets Metabolic Injury

Hypertension and arterial stiffness, the “mechanical-pressure” limb of the M-Quad—raise pulsatile afterload, while cortisol and IR amplify neurohumoral tone (17–19). The interaction of mechanical stress with metabolic inflammation drives concentric hypertrophy, increased LV mass-to-volume ratio, left-atrial (LA) dilation, and pulmonary-vascular coupling abnormalities. Obesity-related HFpEF adds natriuretic-peptide deficiency, expanded plasma volume, and systemic low-grade inflammation (18–20). Chronic diuretic exposure, often necessary for congestion relief, paradoxically depletes intravascular volume, activating the sympathetic nervous system and RAAS, which further elevate cortisol, perpetuating the inflammatory- hypertensive loop and predisposing to chronic kidney disease (CKD) (21–23).

D. The Cortisol–IR–HFpEF Feedback Loop

Cortisol, insulin, and the sympathetic nervous system operate in a self-reinforcing circuit. Chronic stress elevates cortisol, which increases insulin and visceral adiposity; insulin resistance in turn stimulates ACTH and adrenal cortisol synthesis, completing the loop (24, 25). The result is sustained RAAS activation, endothelial dysfunction, and myocardial fibrosis. This feedback sustains the HFpEF substrate even in the absence of obstructive coronary disease.

E. Phenotyping and Diagnostics: Detect the Terrain, Not Just the Ejection Fraction

Echocardiography reveals elevated E/e′ ratios, LA enlargement, and abnormal strain patterns despite preserved EF (26). Exercise echocardiography unmasks exertional elevation of filling pressures when resting indices are borderline (26, 27). Natriuretic peptides are useful but often blunted in obesity; interpretation requires consideration of body composition (20, 28).

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) demonstrates reduced peak VO₂, early anaerobic threshold, and elevated VE/VCO₂ slope, indicating impaired oxygen delivery and utilization (27).

Cardiac MRI with T1 mapping and extracellular-volume quantification provides precise assessment of interstitial fibrosis and steatosis, while PET or perfusion imaging can identify microvascular dysfunction (29, 30).

Upstream metabolic testing- OGTT with fasting/1-h/2-h insulin, triglyceride/HDL ratio, and waist-to-hip measurements, reveals IR even in “non-diabetic” HFpEF. As Einstein reminded us, 'Not everything that can be measured is important, and not everything important can be measured'; insulin resistance exemplifies this invisible but driving pathology.

F. Foundational Terrain Correction

Weight reduction, particularly of visceral fat, combined with structured aerobic and resistance exercise improves diastolic function, vascular stiffness, and blood pressure (22). Nutrient-dense, anti-inflammatory diets that enhance insulin sensitivity and support short-chain fatty-acid (SCFA) production restore endothelial health, autonomic balance, and metabolic flexibility. Optimizing sleep and modulating chronic stress physiology directly attenuate the cortisol–sympathetic axis.

However, the standard lifestyle advice, “eat better, move more, lose weight”, often collides with the underlying hormonal terrain. Cortisol excess induces sarcopenia through protein catabolism and amino-acid oxidation, while insulin resistance starves skeletal muscle of glucose and ketone utilization, forcing reliance on anaerobic glycolysis for ATP production. The muscle becomes metabolically inefficient, generating lactate rather than sustained oxidative energy. Loss of lean mass reduces insulin-responsive tissue, worsening IR and perpetuating the cycle.

Metabolic fuel rebalancing is therefore essential. Lowering chronic hyperinsulinemia restores hepatic ketogenesis and mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation, allowing the heart, skeletal muscle, and brain to access cleaner, higher-yield energy substrates. Contrary to long-held misconceptions, the fat we eat is not the fat that clogs our arteries; rather, chronic hyperinsulinemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress drive atherogenesis. Diets emphasizing nutrient-dense, unprocessed fats and reduced refined carbohydrate slower insulin secretion, improve satiety, and shift metabolism toward fat utilization, enhancing mitochondrial efficiency and sustainable weight loss. In this physiologic state, “when we eat fat, we burn fat.” The metabolic system transitions from storage to utilization, embodying the biochemical essence of terrain recovery: insulin down, oxidation up, and metabolism flexible once again.

G. Pharmacologic and Adjunct Therapies

SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin) reduce HF hospitalization and improve quality of life through natriuresis, interstitial-fluid reduction, improved renal–cardiac coupling, and enhanced ketone availability (31–33).

RAAS modulation (ACEi/ARB, ARNI) remains foundational for afterload reduction; sacubitril/valsartan demonstrated benefit in lower-EF and female subgroups in PARAGONHF (34, 35).

Mineralocorticoid-receptor antagonists (spironolactone, eplerenone) show benefit in patients with elevated fibrosis or aldosterone tone (36).

GLP-1 receptor agonists promote weight loss, reduce inflammation, and improve vascular function (37).

Beta-blockers should be individualized to address chronotropic incompetence and atrial arrhythmias, avoiding excessive bradycardia.

Diuretics relieve congestion but require caution to prevent excessive preload depletion and reflex neurohormonal activation.

Addressing OSA, aldosterone excess, and cortisol dysregulation complements the metabolic core.

H. Integrating HFpEF into the M-Quad

Metabolism (insulin resistance) generates fuel inflexibility, microvascular inflammation, and energetic failure.

Maladaptive cortisol amplifies insulin resistance, RAAS activation, and fibrosis. Mechanical pressure from hypertension cements structural remodeling. Myocardial remodeling, HFpEF, is the final common pathway, yet it remains modifiable when upstream engines are identified and corrected.

The imperative is clear: treat the terrain, not just the phenotype. When we intervene precisely and early at the metabolic core, effects are amplified downstream—transforming disease management into disease reversal. This is precision cardiovascular medicine: acting with purpose before irreversible damage occurs.

Key References

Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction through systemic inflammation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(4):263–271.

Sharma K, Kass DA. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: mechanisms, biomarkers, and therapy. Circ Res. 2014;115(1):79–96.

Shah SJ et al. Insulin resistance and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J. 2022;43(8):672–686.

Ferrannini E et al. Metabolic mechanisms of HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(32):3189–3200.

Borlaug BA. Mechanisms and treatment of HFpEF. Nat Rev Cardiol.2014;11(9):507–515.

Mohammed SF et al. Coronary microvascular rarefaction and myocardial fibrosis in HFpEF. Circulation. 2015;131(6):550–559.

Lam CSP et al. Obesity and HFpEF. Circulation. 2018;138(2):114–125.

Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and cardiovascular disease. Eur J Endocrinol.2007;157(5):545– 559.

Isidori AM et al. Cardiovascular involvement in Cushing’s syndrome: new insights into pathogenesis. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173(1):R1–R8.

Folkers K et al. Evidence that coenzyme Q10 improves efficiency of oxidative phosphorylation in heart failure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82(3):901–904.

Marcoff L, Thompson PD. The role of CoQ10 in statin-associated myopathy: a review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(23):2231–2237.

El-Mir MY et al. Dimethylbiguanide inhibits cell respiration via an effect on the respiratory chain complex I. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(1):223–228.

Rena G, Hardie DG, Pearson ER. The mechanisms of action of metformin. Diabetologia. 2017;60(9):1577–1585.

Franssen C et al. Myocardial microvascular inflammatory–NO–cGMP–PKG pathway in HFpEF. Cardiovasc Res. 2016;111(1):1–8.

Nieuwdorp M et al. The endothelial glycocalyx: a potential barrier between health and vascular disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16(5):507–511.

Westermann D et al. Endothelial inflammation in HFpEF: role of systemic comorbidities. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(17):2187–2195.

Solomon SD et al. PARAGON-HF trial: sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF. N Engl J Med.2019;381(17):1609–1620.

Wang TJ et al. Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation.2004;109(5):594–600.

Reddy YNV et al. Comprehensive noninvasive and invasive assessment of HFpEF. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(4):435–450.

Kitzman DW et al. Exercise training in older patients with HFpEF. Circ Heart Fail.2010;3(6):659–667.

Hall JE et al. Obesity-induced hypertension: interaction of neurohumoral and renal mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116(6):991–1006.

Neter JE et al. Influence of weight reduction on blood pressure: a meta-analysis. Hypertension. 2003;42(5):878–884.

Go AS et al. Chronic kidney disease and risks of death, cardiovascular events, and hospitalization. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1296–1305.

Whitworth JA, Williamson PM, Mangos G, Kelly JJ. Cardiovascular consequences of cortisol excess. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(4):291–299.

Esler M, Lambert E, Jennings G. Sympathetic nervous system and insulin resistance: an interdependent relationship. Diabetologia. 2008;51(5):857–864.

Zile MR et al. Diastolic stiffness mechanisms in HFpEF. Circulation.2004;109(18):2391– 2397.

Pieske B et al. Imaging and biomarkers in HFpEF. Card Fail Rev. 2018;4(1):15–21.

Das SR et al. Body mass, composition, and natriuretic peptides: the Dallas Heart Study. Circulation. 2005;112(14):2163–2168.

Wong TC et al. T1 mapping and extracellular volume in heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(18):185–194.

Taqueti VR et al. Coronary microvascular dysfunction and future risk of HFpEF. Circulation. 2018;138(9):864–875.

Anker SD et al. Empagliflozin in HFpEF (EMPEROR-Preserved). N Engl J Med.2021;385(16):1451–1461.

Solomon SD et al. Dapagliflozin in HFpEF (DELIVER). N Engl J Med.2022;387(11):1089– 1098.

Verma S, McMurray JJV. SGLT2 inhibitors and mechanisms of cardiovascular benefit. Diabetologia. 2018;61(10):2108–2127.

McMurray JJV et al. Subgroup analysis of sacubitril/valsartan in HF with EF ≥45%. Circulation. 2020;141(2):111–121.

Pitt B et al. Spironolactone for HFpEF (TOPCAT). N Engl J Med.2014;370(15):1383–1392.

Zannad F, Ferreira JP, Pitt B. MRAs in heart failure: physiology, outcomes, and patient selection. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(15):1522–1536.

Sattar N et al. GLP-1 receptor agonists and cardiovascular outcomes. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(10):653–662.

Section 6 — The M-Quad: A Single Axis, Not Four Diseases

Reclaiming the Focus of Modern Medicine

Before a patient visits a cardiologist, an endocrinologist, or even a heart-failure clinic, evaluation should begin through a cardiometabolic lens. The cardiometabolic physician occupies the critical upstream position where disease originates, at the intersection of metabolism, stress physiology, and vascular biology, long before hypertension, dysglycemia, or diastolic dysfunction appear. Yet contemporary medicine continues to view these as isolated disorders.

This fragmented approach neglects the truth that the human body does not function in isolation. Its systems, metabolic, endocrine, inflammatory, and hemodynamic, operate as an interconnected network. To restore health, medicine must refocus its direction toward upstream recognition and intervention, identifying terrain dysfunction before it manifests as structural disease.

The M-Quad: Foundational Root of Cardiometabolic Medicine

The M-Quad represents the foundational framework of modern cardiometabolic medicine. It integrates four domains that were historically separated but are in fact expressions of one biologic process:

Metabolism - insulin resistance, mitochondrial dysfunction, and loss of fuel flexibility;

Maladaptive Cortisol Response - chronic activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and sympathetic overdrive;

Mechanical Pressure - hemodynamic load, vascular tone, and endothelial injury;

Myocardial Remodeling - energetic starvation, fibrosis, and altered diastolic compliance.

Rather than discrete entities, these form concentric layers of a single cardiometabolic engine. When metabolism falters, cortisol amplifies; when cortisol rises, vascular pressure mounts; and when pressure persists, the myocardium remodels. The sequence produces a progressive terrain of dysfunction, the M-Quad continuum, that links insulin resistance, hypertension, and heart failure within one unifying physiology [1–5].

From Fragmentation to Framework

Despite overwhelming evidence, clinical medicine remains trapped in specialty silos: hypertension clinics, lipid centers, heart-failure programs, endocrine consults. Each addresses a late-stage phenotype, while the upstream metabolic terrain remains unrecognized. Insulin resistance (IR) lies at the center of this web, igniting maladaptive cortisol signaling, sympathetic activation, renal sodium retention, endothelial dysfunction, and ultimately myocardial remodeling [6–9].

The M-Quad thus parallels and extends the cardiorenal-metabolic model, it unifies the mechanisms that precede these diseases. Where the older framework linked kidney, heart, and glucose, the M-Quad reaches deeper, identifying the root drivers that precede all three. It transforms care from reactive management to proactive terrain restoration [10–12].

Shared Pathways Across the Axis

At a molecular level, the M-Quad’s components are inseparable.

Insulin resistance increases sympathetic outflow and activates the renin–angiotensin– aldosterone system (RAAS), raising vascular tone and blood pressure [13–15].

Cortisol excess augments adrenergic receptor sensitivity, promotes visceral adiposity, and amplifies inflammatory cytokines [16–18].

Mechanical pressure from chronic hypertension induces oxidative stress and fibrotic signaling through MAPK and TGF-β cascades [19, 20].

Myocardial remodeling reflects the culmination of these processes: mitochondrial inflexibility, reduced nitric-oxide bioavailability, and titin hypophosphorylation producing diastolic stiffness [21–23].

These feedback loops create a self-sustaining metabolic storm, explaining why insulin resistance, cortisol dysregulation, and vascular remodeling often coexist decades before the first abnormal laboratory result.

Why the Siloed Model Fails

Traditional care treats these downstream manifestations as separate diseases. Hypertension is labeled “essential” when it is an early expression of insulin resistance [24]. HFpEF is deemed “non-ischemic” though it originates in metabolic fuel starvation [25]. Cortisol dysregulation is dismissed as “stress” rather than a biochemical amplifier of vascular injury [26].

This piecemeal paradigm yields escalating polypharmacy without addressing the source. In contrast, the M-Quad reframes these not as discrete disorders but as temporal stages of one chronic terrain dysfunction.

A Systems-Biology View of Disease

The M-Quad connects cellular metabolism to organ physiology through common biochemical threads: insulin, cortisol, nitric-oxide signaling, mitochondrial energetics, and inflammatory transcription factors.

Vascular system: insulin resistance and cortisol suppress endothelial nitric-oxide synthase and shear-mediated vasodilation [27].

Renal system: hyperinsulinemia and angiotensin II enhance sodium reabsorption, expand plasma volume, and sustain RAAS tone [28].

Cardiac system: mitochondrial inflexibility favors fatty-acid oxidation over glucose and ketone utilization, increasing oxygen cost and producing energetic starvation [29].

Neuroendocrine system: chronic sympathetic activation sustains renin and cortisol secretion, closing the feedback loop [30].

Each organ expresses the same disturbance through its own phenotype — vascular stiffness, albuminuria, diastolic dysfunction, or anxiety — but all arise from a shared metabolic origin.

Clinical Implications: Treating the System, Not the Symptom

Adopting the M-Quad framework reshapes diagnostic and therapeutic priorities.

Diagnostics must extend beyond glucose and LDL, incorporating insulin-response curves (OGTT with insulin), triglyceride-to-HDL ratio, waist-to-hip ratio, and indices of cortisol or RAAS activation [31–33].

Therapeutics should pursue terrain correction, lowering insulin and cortisol levels, restoring metabolic flexibility, and repairing endothelial health, rather than merely normalizing blood pressure or A1c.

Outcomes must reflect restoration of system health: improved insulin sensitivity, reduced inflammation, and mitochondrial recovery. When the metabolic engine stabilizes, downstream manifestations regress. Without the fire, the sparks fade.

The Imperative Role of the Cardiometabolic Specialist

Recognition of the cardiometabolic specialist must precede referral to cardiology, endocrinology, or the heart-failure clinic. This clinician operates at the entry point of the disease cascade, identifying and correcting dysfunction before fragmentation occurs. When upstream correction succeeds, the trajectory of hypertension, heart failure, and metabolic disease can be reversed. When it fails, or when the specialty is unrecognized, patients are divided among hypertensive, endocrine, and heart-failure programs that treat symptoms of the same pathology [34–36].

Every patient with resistant hypertension, borderline glucose, visceral adiposity, or chronic stress physiology should first be evaluated by a physician fluent in insulin signaling, stress biochemistry, and vascular energetics.

Cardiometabolic medicine is not an adjunct discipline; it is the foundation of modern chronic disease prevention. It is where medicine must go next.

Key References

Ferrannini E, Natali A. Essential Hypertension, Metabolic Disorders, and Insulin Resistance. Am Heart J. 1991;121:1274–1282.

Reaven GM. Insulin Resistance: The Link Between Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:875–892.

Hall JE et al. Obesity-Induced Hypertension: Interaction of Neurohumoral and Renal Mechanisms. Circ Res. 2015;116:991–1006.

DeFronzo RA. Insulin Resistance, Lipotoxicity, and the Metabolic Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1092–1100.

Petersen KF, Shulman GI. Mechanisms of Insulin Action and Insulin Resistance.Physiol Rev. 2018;98:2133–2223.

Julius S et al. Early-Phase Insulin Response and the Pathogenesis of Hypertension.J Hypertens. 1991;9:1107–1114.

Grassi G et al. Sympathetic Activation in Obese Normotensive Subjects.Hypertension. 1995;25:560–563.

Anderson EA et al. Hyperinsulinemia Produces Sympathetic Neural Activation in Humans. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:2246–2252.

Schlaich MP et al. Sympathetic Neural Mechanisms in Human Hypertension. Circ Res. 2015;116:976–990.

Hall JE, Brands MW, Henegar JR. Mechanisms of Hypertension and Kidney Disease in Obesity. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;892:91–107.

Vasan RS et al. Cardiometabolic Risk: A New Framework for Prevention. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1233–1239.

McMurray JJV et al. Cardiorenal-Metabolic Disease: Integrating Mechanisms and Care. Lancet. 2022;399:1689–1702.

Brands MW et al. Sustained Hyperinsulinemia Increases Arterial Pressure in Conscious Rats. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:R764–R768.

Goodfriend TL et al. Plasma Aldosterone, Lipoproteins, Obesity, and Insulin Resistance in Humans. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995;52:213–217.

Engeli S et al. The Adipose-Tissue Renin–Angiotensin–Aldosterone System: Role in the Metabolic Syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1999–2004.

Walker BR. Glucocorticoids and Cardiovascular Disease. Eur J Endocrinol.2007;157:545– 559.

Isidori AM et al. Cardiovascular Involvement in Cushing’s Syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2015;173:R1–R8.

Steptoe A et al. Psychosocial Stress and Cardiometabolic Disease Risk. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2023;20:17–32.

Muniyappa R et al. Cardiovascular Actions of Insulin. Endocr Rev. 2007;28:463–491.

Brownlee M. Advanced Protein Glycosylation in Diabetes and Aging. Annu Rev Med. 1995;46:223–234.

Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C. A Novel Paradigm for HFpEF. J Am Coll Cardiol.2013;62:263–271.

Sharma K, Kass DA. Mechanisms, Biomarkers, and Therapy of HFpEF. Circ Res.2014;115:79–96.

Shah SJ et al. Insulin Resistance and HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2022;43:672–686.

Ferrannini E et al. Insulin Resistance in Essential Hypertension. J Hypertens.1987;5:S121– S126.

Lam CSP et al. Obesity and HFpEF. Circulation. 2018;138:114–125.

Esler M et al. Sympathetic Nerve Biology in Essential Hypertension. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2001;28:986–989.

Nieuwdorp M et al. The Endothelial Glycocalyx: A Barrier Between Health and Disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:507–511.

DeFronzo RA et al. Effect of Insulin on Renal Sodium Handling in Man. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:845–855.

Ferrannini E et al. Metabolic Mechanisms of HFpEF. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:3189–3200.

McEwen BS, Gianaros PJ. Central Mechanisms of Stress-Induced Cardiometabolic Disease. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24:168–176.

Abdul-Ghani MA et al. The 1-Hour Plasma Glucose: A Strong Predictor of Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1650–1655.

Reaven GM. The Triglyceride/HDL Ratio as an Insulin-Resistance Marker. Clin Chem. 2001;47:433–439.

Alberti KG et al. Harmonizing the Metabolic Syndrome Definition. Circulation.2009;120:1640–1645. 34. 35. 36. 1. 2. 3. 4.

Ballantyne CM et al. Cardiometabolic Medicine: The New Frontline. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:1335–1349.

Fuster V. Integration of Cardiovascular and Metabolic Care: The Future of Medicine.JACC. 2021;78:1–5.

Bhatt DL. Cardiometabolic Continuum: Time for Upstream Intervention. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2051–2053

Section 7 — Therapeutic Landscape: Targeting Insulin Resistance, Calming Cortisol, and Protecting the Terrain

The Case for Upstream Intervention

By the time resistant hypertension, HFpEF, or biochemical hypercortisolism is recognized, the M-Quad has often been active for years, insulin resistance (IR) fueling SNS and RAAS activation, cortisol amplifying visceral adiposity, mechanical pressure remodeling the vasculature, and myocardial energetics deteriorating [1–7].

Guideline algorithms that chase BP, LDL, or EF thresholds overlook this terrain, explaining why medication stacking yields diminishing returns [5–7].

In contrast, early recognition and reversal of IR and cortisol dysregulation can change the natural history of disease [8–14].

Sequence that fits the biology

Identify and reverse IR early, OGTT with insulin, TG/HDL, waist–hip ratio.

Evaluate cortisol physiology and stress load (clinical or biochemical screens for subclinical Cushing’s, OSA, inflammatory drivers).

Reduce hemodynamic pressure by lowering metabolic pressors (IR, SNS, RAAS, aldosterone) in addition to standard agents.

Restore energetics and endothelial health to prevent or reverse myocardial remodeling [15–17].

NESS First—but Acknowledge Terrain Drag

Foundational non-pharmacologic therapy, NESS (nutrition, exercise, sleep, spirituality/ socialization), is the formative pillar for restoring insulin sensitivity and metabolic flexibility. Yet late-stage terrain features, chronic hypercortisolism, entrenched IR, and cortisol-driven sarcopenia, can blunt exercise tolerance through protein catabolism and substrate deprivation. Effective programs therefore combine graded, resistance-forward exercise with protein repletion, circadian-aligned nutrition, restorative sleep, and stress-modulating practices to calm the HPA axis while upstream therapies begin reversing the metabolic terrain [18–30].

Pharmacologic Precision: Reinforcing the Terrain: Positive (+) Negative (-) Neutral (=)

Insulin-Resistance and Remodeling Directed Agents

GLP-1 receptor agonists (liraglutide / semaglutide) — ↓ IR, visceral fat, BP, inflammation; CV benefit proven (LEADER, SELECT). M-Quad: (+) [31–34].

SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin / dapagliflozin) — ↓ BP, ↓ interstitial congestion; HF benefit in HFpEF and HFrEF independent of diabetes. M-Quad: (+) [35–38].

PPAR-γ agonist (pioglitazone) — ↑ insulin sensitivity and NO; edema risk → avoid in decompensated HF. M-Quad:(+) / (=) [39–41].

Bromocriptine-QR (dopaminergic reset) — modulates early-morning SNS/cortisol rhythms; metabolic gain, modest BP reduction. M-Quad:(+) / (=) [42,43].

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (spironolactone / eplerenone) — ↓ aldosterone load and fibrosis; useful in RHTN and select HFpEF. M-Quad: (+) [44,45].

Cortisol-Directed Therapies

Mifepristone (GR antagonist) — improves glycemia, BP, weight in Cushing’s; monitor K⁺ and adrenal reserve. M-Quad:(+) [60–62].

Osilodrostat / Levoketoconazole / Metyrapone — block cortisol synthesis; improve glycemia and BP; class-specific AEs (QTc, LFTs, hypokalemia). M-Quad: (+)/ (=) [63–68].

Pasireotide / Cabergoline — pituitary-directed; pasireotide may raise glucose (=); cabergoline often metabolically neutral or beneficial (+) [69–71].

Clinical note: In resistant hypertension or HFpEF with features of hypercortisolism (centripetal obesity, proximal myopathy, hypokalemia, OSA, depression), screen for autonomous cortisol secretion, directed therapy can unwind the entire M-Quad loop.

Help versus Harm to the M-Quad

Insulin-sensitizing agents (GLP-1 RA, SGLT2i, PPAR-γ, bromocriptine-QR) tend to be MQuad positive: they lower IR, BP, visceral fat, and SNS tone, and improve endothelial function and outcomes.

Exogenous long-acting insulin (-) : used reflexively for modest dysglycemia, it exacerbates hyperinsulinemia, sodium retention, and sympathetic drive, worsening energetic inflexibility and mechanical load [47–50].

Metformin (=) : beneficial for glycemia but its complex-I inhibition may blunt training adaptations in some; neutral on insulin signaling per se [51–54].

Statins (no ASCVD) (=) / (-) : life-saving with plaque, but in plaque-negative terrain may worsen IR and reduce CoQ10/mitochondrial efficiency [55–59].

Sulfonylureas (-)(-) "Pushing the Rusty Door Harder"

Sulfonylureas lower glucose by forcing β-cell insulin release but do not correct IR. They heighten hyperinsulinemia, promote weight gain, and are linked to β-cell burnout, myocardial infarction, all-cause mortality, and dementia [72–78]. Large BMJ and Veterans Health System analyses confirm higher cardiovascular and cognitive risk compared with metformin or TZDs, especially when metformin is discontinued [72–75]. Accordingly, ADA Standards of Care (2025) recommend GLP-1 RA and SGLT2i ahead of sulfonylureas for patients with CV or renal risk [79].

Clinical takeaway: Lowering glucose with insulin or secretagogues is like forcing a rusty door open by pushing harder. The rust is insulin resistance. Oil the hinge—restore insulin signaling and metabolic flexibility—rather than deepening hyperinsulinemia.

Summary Tables

Table 1 – Therapeutic Classes Mapped to M-Quad Axes